Page 2

| Parent | Perpetuation of testimony by Witnesses in U. S. for Presentation to the International Military Tribunal |

|---|---|

| Date | 18 June 1945 |

| Language | English |

| Collection | Tavenner Papers & IMTFE Official Records |

| Box | Box 3 |

| Folder | General Reports and Memoranda from June 1946 |

| Repository | University of Virginia Law Library |

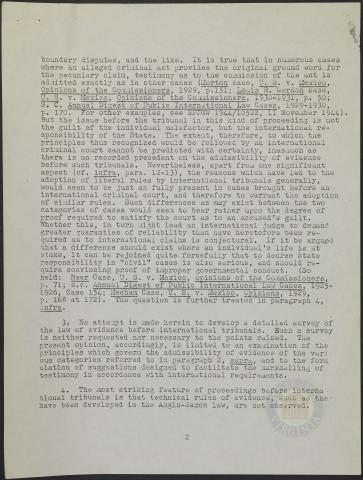

boundary disputes, and the like. It is true that in numerous cases

where an alleged criminal act provides the original ground word for

the pecuniary claim, testimony as to the commission of the act is

admitted exactly as in other cases (Morton case, U. S. v. Mexico,

Opinions of the Commissioners, 1929, p.151; Louis B. Gordon case,

U. S. v. Mexico, Opinions of the Commissioners, 1930-1931, p. 50;

S. C. Annual Digest of Public International Law Cases, 1929-1930,

p. 170. For other examples, see SPJGW 1944/10522, 11 November 1944).

But the issue before the tribunal in this kind of proceeding is not

the guilt of the individual malefactor, but the international responsibility of the State. The extent, therefore, to which tne

principles thus recognized would be followed by an international

criminal court cannot be predicted with certainty, inasmuch as

there is no recorded precedent on the admissibility of evidence

before such tribunals. Nevertheless, apart from one significant

aspect (cf. infra, pars. 12-13), the reasons which have led to the

adoption of liberal rules by international tribunals generally,

would seem to be just as fully present in cases brought before an

international criminal court, and therefore to warrant the adoption

of similar rules. Such differences as may exist between the two

categories of cases would seem to bear rather upon the degree of

proof required to satisfy the court as to an accused's guilt.

Whether this, in turn might lead an international judge to demand

greater guaranties of reliability than have heretofore been required as to international claims is conjectural. If it be argued

that a difference should exist where an individual's life is at

stake, it can be rejoined quite forcefully that to decree State

responsibility in "civil" cases is also serious, and should re-

require convincing proof of improper governmental conduct. (So

Mexico, Opinions of the Commissioners,

held: Neer Case, U.S. v. Mexico, Opinions of the Commissioners, p. 71; s.c. Annual Digest of Public Internaitonal Law Cases, 1925-1926, Case 154; Mecham Case, U. S. v. Mexico, opinions, 1929, p. 168 at 172). The question is further treated in paragraph 4,

infra.

3. No attempt is made herein to develop a detailed survey of

the law of evidence before international tribunals. Such a survey

is neither requested nor necessary to the points raised. The

present opinion, accordingly, is limited to an examination of the

principles which govern the admissibility of evidence of the vari-

ous categories referred to in paragraph 2, supra, and to the form-

ulation of suggestions designed to facilitate the marshalling of

testimony in accordance with international requirements.

4. The most striking feature of proceedings before interna-

tional tribunals is that technical rules of evidence, such as they

have been developed in the Anglo-Saxon law, are not observed.